Sade/Surreal. Der Marquis de Sade und die erotische Fantasie des Surrealismus …

30.11.2001 – 03.03.2002

Curated by Tobia Bezzola.

Location Moser-Bau (2. Stock).

Curated by Tobia Bezzola.

Location Moser-Bau (2. Stock).

The first exhibition of its kind, which built a bridge between the notorious writer and his influence on visual art. Considering the explicitly pornographic character of the Marquis de Sade’s work, a breach in the taboo, which had fallen due against the background of the explosiveness of his writing and its influence on one of the most important streams of art in the 20th century, namely Surrealism.

Full title

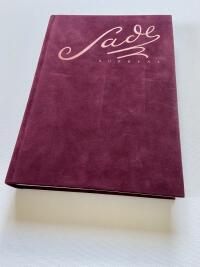

Sade/Surreal. Der Marquis de Sade und die erotische Fantasie des Surrealismus in Text und BildIt was a world premiere: Although often (and not rarely inaccurately) quoted, the original letters of the Marquis de Sade from his 27 years of imprisonment were on public display in the original for the first time – in a glass case 27 meters long. Because permission from the donor, the Bibliothèque de l’Arsenal (Paris), arrived only very shortly before the opening of the exhibition, these exhibits could not be reproduced in their entirety in the catalog, but only as reference material (p. 27, 31, 35). Quite apart from their cult character, the autographs reveal a great deal about Sade’s creative production dynamic – which was very fortunate for various areas of research. In the exhibition catalog, suggestively bound in red velvet, Tobia Bezzola, the in-house member of the team of curators, recorded unmistakably what has made, to this day, the Marquis de Sade so special and simultaneously so difficult to grasp: ‘Sade the man of letters, Sade the dilletante, Sade the revolutionary, Sade the reactionary, Sade the psychopath, Sade the psychologist, Sade the Enlightenment man, Sade the fascist, Sade the philosopher, Sade the dimwit, Sade the bore, Sade the sensation… Few historical figures attract to this day such contrary interpretations in posterity.’

On closer examination of the media response, it becomes clear that the journalists acknowledged, and usually also valued, the achievement in research, the dramaturgical precision and indeed the courage required for such an exhibition. For example, Lilith Frey wrote for the tabloid ‘Blick’ (30.11.2001), from whom one might not perhaps have expected it, in terms of praise: ‘Remarkable is this beautiful, delicate writing hand. [...] The bright lighting and the mostly small size of the images make it easier for the viewer to maintain distance. Presented so modestly, they lose something of their aggressiveness and repulsive obscenity. The viewer’s imagination is not violated. On the contrary he can let it develop independently. That is the secret of the cleverly staged exhibition.’ One of the most spectacular exhibits, and therefore one of those most frequently reproduced ones in the press coverage was Louis Soubrier’s ‘Chaise sexuelle’, which was manufactured in three examples in 1890 (including one for Edward VII) – but which Sade, however, never could have seen.

[Cathérine Hug]

'If we can read him today as a real pornosopher, as a producer of writing and ideas with linguistic wit, black humor and imagination, the Surrealists were those who opened our eyes and senses for this new Sade and his bewildering diversity.'Stefan Zweifel and Michael Pfister

93 days

34 Artists

34 Artists

1/2

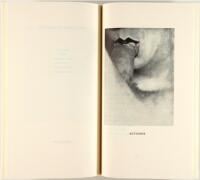

exhibition catalog

2/2

exhibition catalog

1/2