Der Hang zum Gesamtkunstwerk. Europäische Utopien seit 1800

11.02.1983 – 30.04.1983

Curated by Harald Szeemann and Toni Stooss.

Location Pfister-Bau (Grosser Ausstellungssaal, ehem. Bührlesaal).

Curated by Harald Szeemann and Toni Stooss.

Location Pfister-Bau (Grosser Ausstellungssaal, ehem. Bührlesaal).

Conceptually, the exhibition was not simply an extension of Richard Wagner’s way of thinking to other epochs and disciplines but swarmed out, although critically, to absorb the dialectic of total art and totalitarianism into the reflections and pointed out the typical European element that is anchored in the concept.

‘Giving all, wanting to discover a connection with the universe or to achieve a concentrated universe is only a tendency, a confession, an obsession, a distilment of art and the wish for salvation. The total work of art doesn’t exist.’ In this way the curator introduces the idea of the ‘total work of art’ (Gesamtkunstwerk) into the 512-page exhibition catalog, which is not without a certain degree of complexity. Shortly afterwards, of course, the curator also makes the connection to Richard Wagner, the famous composer, who first coined the expression in 1850, in his Zurich writings. Conceptually, however, the exhibition was not simply an extension of this way of thinking to other epochs and disciplines but swarmed out, although critically, to absorb the dialectic of total art and totalitarianism into the reflections and pointed out the typical European element that is anchored in the concept. The exhibition was formally inaugurated by the former Federal President Walter Scheel. In addition to many famous artists, such as Joseph Beuys and Markus Raetz, the former German Federal President Helmut Schmidt was among the guests of the opening ceremony. The reception of the exhibition in the press was mixed, which is not especially surprising considering the exalted claims raised by the curator and his authors in the catalog (including Bazon Brock and Jean Clair), for theses of this complexity require a lot of time for recapitulation, time which is not normally available to journalists (and often also visitors). In all this, one review stands out in particular, because it represents a hatchet job on one of the heavyweights in the local art scene – Max Bill – and fails to recognize the great achievement of this exhibition: to weave around 300 top-level exhibits from a wide range of disciplines and from numerous donors into such association-rich stories that their common denominator, and thus the larger view, as well as the common European element can be understood (‘ZüriWoche’, 12.02.1983).

In formal terms, this exhibition demonstrated that artworks are not autonomous but are always embedded in a larger explanatory context and, consequently, need to be presented installatively, meaning spatially. These days ‘installation art’ is an established concept but in those days it was applied only to individual artists, such as Kurt Schwitters or Joseph Beuys. The path-breaking exhibition, which is one of the most legendary from Szeemann’s kitchen, travelled after Zurich to the Kunsthalle Düsseldorf and into the Museum of the 20th century in Vienna. With 67,386 entries, the press of visitors was in the middle of the range (the Ferdinand Hodler exhibition in the same year, for example, recorded 163,380 entries). Accompanying the exhibition there was also a wide-ranging, mostly musical program of events, including the greatly appreciated appearance of experimental musician Laurie Anderson at the Volkshaus Zürich.

[Cathérine Hug]

A 'unique European idea', which will hopefully stimulate discussion about the cultural unity of Europe and strengthen the wish for a Europe united in freedom and peace and not a 'managed' Europe.Walter Scheel

78 days

48 Artists

48 Artists

1/3

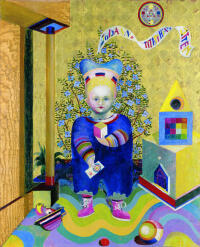

exhibition poster

Design: Markus Raetz

Design: Markus Raetz

2/3

press

ZüriWoche, 24.3.1983

ZüriWoche, 24.3.1983

3/3

press

La Suisse, 11.2.1983

La Suisse, 11.2.1983

1/3